<section label="section-further-reading">

<title>Further Reading</title>

<subsection>

<title>Specialized Subdivisions</title>

<p>

In a longer work you might wish to have some references on a per-chapter basis,

or similar.

You can make a

<q>references</q>

subdivision anywhere to hold bibliographic items,

and you can reference the items like any other item.

For example,

we can cite the article below <xref ref="biblio-beezer-fcla" detail="Chapter R"/>,

included an indication that a specific chapter may be relevant.

</p>

</subsection>

<exercises>

<title>Exercises</title>

<exercise xml:id="exercises-null-problem">

<statement>

<p>

No problem here, but the next two are in an

<q>exercise group</q>

with an introduction and a conclusion,

along with an optional title.

The two problems of the exercise group should be indented some to indicate the grouping.

</p>

<p>

N.B. An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> is meant to hold a collection of (short) exercises with common, shared,

instructions.

Do not use this structure to subdivide an <tag>exercises</tag> division,

as you will eventually be disappointed.

Instead, use the available, but under development as of 2019-11-02,

<tag>subexercises</tag>, which <em>requires</em> a <tag>title</tag>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-problems">

<title>Two Derivative Problems</title>

<idx><h>exercise group</h><h>two derivatives</h></idx>

<introduction>

<p>

In the next two problems compute the indicated derivative.

</p>

<image source="images/cubic-function.png" width="30%"/>

<p>

You could

<q>connect</q>

the image above with the exercises following as part of this <c>introduction</c> for the <c>exercisegroup</c>.

</p>

</introduction>

<!-- This exercise has no solutions, so we can dispense with the "statement" structure -->

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise xml:id="exercises-cosine-derivative">

<idx><h>derivative</h><h>cosine</h></idx>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Note that the previous two problems used very different notation for the function and the resulting derivative.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<p>

This isn't really an exercise,

but an explanation that the next <tag>exercisegroup</tag> has a title and no <tag>introduction</tag>,

which once resulted in some aberrant formatting in <latex/> output.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-more-problems">

<title>Two More Derivative Problems</title>

<introduction>

<p>

Some common instructions would go here in the <tag>introduction</tag>

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<p>

Compute <m>\int 3x^2\,dx</m>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

One of the few things you can place inside of mathematics is a

<q>fill-in</q>

blank.

<idx><h>fill-in blank</h></idx>

We demonstrate a few scenarios here.

See details on syntax in <xref ref="subsection-paragraph-markup" text="type-global"/><ndash/>the use is identical within mathematics.

<ul>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (short, space for <m>x</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin fill="x"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (default, space for <m>XXX</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside exponents and subscripts

(each is space for the string

<q>12</q>).

In this case,

be sure to wrap your exponents and subscripts in braces,

as would be good <latex/> practice anyway:

<m>x^{5+<fillin fill="12"/>}\,y_{<fillin fill="12"/>}</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (too long for this line probably, 40 characters long):

<m>\tan(<fillin fill="Mxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

So use inside a displayed equation

<md>

16\log\space<fillin fill="1-x^2"/>

</md>

like this one.

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside the second line of a multi-line display:

<md>

<mrow>y &= x^7\,x^8</mrow>

<mrow>&= x^{<fillin fill="15"/>}</mrow>

</md>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

This fillin has the historical <attr>characters</attr> attribute for a fillin inside math:

<m>1+<fillin characters="5"/>+4=10</m>,

which may be more convenient,

but may not side properly in places like subscripts,

superscripts, fractions, limits of integrals, and so on.

</p>

</li>

</ul>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercises>

<exercises xml:id="exercises-section-multiple">

<title>More Exercises</title>

<introduction>

<p>

This exercises section should start on a new page in PDF output if the standard publisher file is used.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

This is not a real exercise,

we just want to explain that this is another subsection of exercises,

which has two consecutive exercise groups.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to first exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Only exercise of first group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to first exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to second exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

First exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Second exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to second exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercisegroup cols="4">

<introduction>

<p>

An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> can have a <c>cols</c> attribute taking a value from 2<ndash/>6.

Exercises will progress by row, in so many columns.

On a small screen,

the HTML exercises may reorganize into fewer columns.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

<p>

And a bit more.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

This feature was designed with short

<q>drill</q>

exercises in mind.

With long exercises,

or exercises with long hints, answers, or solutions,

there is a risk that the <latex/> output will have bad page breaks in the vicinity

(just before)

such an exercise that occupies too much vertical space.

Edit, rearrange,

or use fewer columns to see if the situation improves.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Make a table and a graph for the function <m>f(x)=x^2</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<sidebyside>

<tabular halign="center">

<row header="yes" bottom="medium">

<cell><m>x</m></cell>

<cell><m>f(x)</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>2</m></cell>

<cell><m>4</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>3</m></cell>

<cell><m>9</m></cell>

</row>

</tabular>

<image xml:id="x-squared">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}

\begin{axis}

\addplot[domain=-1.5:4, blue, thick, {stealth}-{stealth}] {x^2};

\end{axis}

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</sidebyside>

</answer>

</exercise>

</exercises>

<references xml:id="references-section">

<title>References</title>

<idx><h>references</h><h>within a section</h></idx>

<introduction>

<p>

These items are here to test basic formatting of references.

</p>

</introduction>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-strang-article">

Gilbert Strang,

<title>The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra</title>,

<journal>The American Mathematical Monthly</journal>

November 1993,

<volume>100</volume>

<number>9</number>,

848<ndash/>855.

</biblio>

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="CF">

<author>

J. B. Conrey and D. W. Farmer

</author>

<title>Mean values of <m>L</m>-functions and symmetry</title>

<journal>Internat. Math. Res. Notices</journal>

<number>17</number>

<year>2000</year>

<pages start="883" end="908"/>

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-beezer-fcla">

Robert A. Beezer,

<title>A First Course in Linear Algebra</title>,

3rd Edition, Congruent Press, 2012.

<note>

<p>

An online, open-source<fn>

A gratuitous footnote to test prior bug confusing this with a REMARK-LIKE <tag>note</tag>.

</fn> offering.

</p>

</note>

</biblio>

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="Dav">

<author>

H. Davenport

</author>

<title>Multiplicative Number Theory</title>

<series>GTM</series>

<volume>74</volume>

<publisher>Springer-Verlag New York, NY</publisher>

<year>2000</year>

<pages>xiv+177</pages>

<pubnote>A note may accompany a bibliographic item, such as saying the manuscript is under review. But it cannot contain any formatting.</pubnote>

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional">

Alexander Rosswell,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2020</year>,

<volume>2</volume>

<number>6</number>,

884<ndash/>888.

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional-two">

<ibid/>,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles, Part 2</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2021</year>,

<volume>3</volume>

<number>4</number>,

102<ndash/>103.

</biblio>

<conclusion>

<p>

This is a conclusion, which has not been used very much in this sample.

Did you see that the entry for <xref ref="biblio-beezer-fcla"/> has a short annotation?

So you can make annotated bibliographies easily.

</p>

</conclusion>

</references>

</section>

Section 11 Further Reading

View Source for section

Subsection 11.1 Specialized Subdivisions

View Source for subsection

<subsection>

<title>Specialized Subdivisions</title>

<p>

In a longer work you might wish to have some references on a per-chapter basis,

or similar.

You can make a

<q>references</q>

subdivision anywhere to hold bibliographic items,

and you can reference the items like any other item.

For example,

we can cite the article below <xref ref="biblio-beezer-fcla" detail="Chapter R"/>,

included an indication that a specific chapter may be relevant.

</p>

</subsection>

In a longer work you might wish to have some references on a per-chapter basis, or similar. You can make a “references” subdivision anywhere to hold bibliographic items, and you can reference the items like any other item. For example, we can cite the article below [11.4.3, Chapter R], included an indication that a specific chapter may be relevant.

Exercises 11.2 Exercises

View Source for exercises

<exercises>

<title>Exercises</title>

<exercise xml:id="exercises-null-problem">

<statement>

<p>

No problem here, but the next two are in an

<q>exercise group</q>

with an introduction and a conclusion,

along with an optional title.

The two problems of the exercise group should be indented some to indicate the grouping.

</p>

<p>

N.B. An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> is meant to hold a collection of (short) exercises with common, shared,

instructions.

Do not use this structure to subdivide an <tag>exercises</tag> division,

as you will eventually be disappointed.

Instead, use the available, but under development as of 2019-11-02,

<tag>subexercises</tag>, which <em>requires</em> a <tag>title</tag>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-problems">

<title>Two Derivative Problems</title>

<idx><h>exercise group</h><h>two derivatives</h></idx>

<introduction>

<p>

In the next two problems compute the indicated derivative.

</p>

<image source="images/cubic-function.png" width="30%"/>

<p>

You could

<q>connect</q>

the image above with the exercises following as part of this <c>introduction</c> for the <c>exercisegroup</c>.

</p>

</introduction>

<!-- This exercise has no solutions, so we can dispense with the "statement" structure -->

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise xml:id="exercises-cosine-derivative">

<idx><h>derivative</h><h>cosine</h></idx>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Note that the previous two problems used very different notation for the function and the resulting derivative.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<p>

This isn't really an exercise,

but an explanation that the next <tag>exercisegroup</tag> has a title and no <tag>introduction</tag>,

which once resulted in some aberrant formatting in <latex/> output.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-more-problems">

<title>Two More Derivative Problems</title>

<introduction>

<p>

Some common instructions would go here in the <tag>introduction</tag>

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<p>

Compute <m>\int 3x^2\,dx</m>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

One of the few things you can place inside of mathematics is a

<q>fill-in</q>

blank.

<idx><h>fill-in blank</h></idx>

We demonstrate a few scenarios here.

See details on syntax in <xref ref="subsection-paragraph-markup" text="type-global"/><ndash/>the use is identical within mathematics.

<ul>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (short, space for <m>x</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin fill="x"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (default, space for <m>XXX</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside exponents and subscripts

(each is space for the string

<q>12</q>).

In this case,

be sure to wrap your exponents and subscripts in braces,

as would be good <latex/> practice anyway:

<m>x^{5+<fillin fill="12"/>}\,y_{<fillin fill="12"/>}</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (too long for this line probably, 40 characters long):

<m>\tan(<fillin fill="Mxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

So use inside a displayed equation

<md>

16\log\space<fillin fill="1-x^2"/>

</md>

like this one.

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside the second line of a multi-line display:

<md>

<mrow>y &= x^7\,x^8</mrow>

<mrow>&= x^{<fillin fill="15"/>}</mrow>

</md>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

This fillin has the historical <attr>characters</attr> attribute for a fillin inside math:

<m>1+<fillin characters="5"/>+4=10</m>,

which may be more convenient,

but may not side properly in places like subscripts,

superscripts, fractions, limits of integrals, and so on.

</p>

</li>

</ul>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercises>

1.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="exercises-null-problem">

<statement>

<p>

No problem here, but the next two are in an

<q>exercise group</q>

with an introduction and a conclusion,

along with an optional title.

The two problems of the exercise group should be indented some to indicate the grouping.

</p>

<p>

N.B. An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> is meant to hold a collection of (short) exercises with common, shared,

instructions.

Do not use this structure to subdivide an <tag>exercises</tag> division,

as you will eventually be disappointed.

Instead, use the available, but under development as of 2019-11-02,

<tag>subexercises</tag>, which <em>requires</em> a <tag>title</tag>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

No problem here, but the next two are in an “exercise group” with an introduction and a conclusion, along with an optional title. The two problems of the exercise group should be indented some to indicate the grouping.

N.B. An

<exercisegroup> is meant to hold a collection of (short) exercises with common, shared, instructions. Do not use this structure to subdivide an <exercises> division, as you will eventually be disappointed. Instead, use the available, but under development as of 2019-11-02, <subexercises>, which requires a <title>.

Two Derivative Problems.

View Source for exercisegroup

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-problems">

<title>Two Derivative Problems</title>

<idx><h>exercise group</h><h>two derivatives</h></idx>

<introduction>

<p>

In the next two problems compute the indicated derivative.

</p>

<image source="images/cubic-function.png" width="30%"/>

<p>

You could

<q>connect</q>

the image above with the exercises following as part of this <c>introduction</c> for the <c>exercisegroup</c>.

</p>

</introduction>

<!-- This exercise has no solutions, so we can dispense with the "statement" structure -->

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise xml:id="exercises-cosine-derivative">

<idx><h>derivative</h><h>cosine</h></idx>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Note that the previous two problems used very different notation for the function and the resulting derivative.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

In the next two problems compute the indicated derivative.

You could “connect” the image above with the exercises following as part of this

introduction for the exercisegroup.

2.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

\(f(x)=x^3\text{,}\) \(\frac{df}{dx}\text{.}\) This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group. For the

phrase-global form, the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the exercises division, and not the enclosing exercisegroup: Exercise 3 of Exercises 11.2.

3.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="exercises-cosine-derivative">

<idx><h>derivative</h><h>cosine</h></idx>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

Note that the previous two problems used very different notation for the function and the resulting derivative.

4.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<p>

This isn't really an exercise,

but an explanation that the next <tag>exercisegroup</tag> has a title and no <tag>introduction</tag>,

which once resulted in some aberrant formatting in <latex/> output.

</p>

</exercise>

This isn’t really an exercise, but an explanation that the next

<exercisegroup> has a title and no <introduction>, which once resulted in some aberrant formatting in LaTeX output.

Two More Derivative Problems.

View Source for exercisegroup

<exercisegroup xml:id="exercisegroup-two-more-problems">

<title>Two More Derivative Problems</title>

<introduction>

<p>

Some common instructions would go here in the <tag>introduction</tag>

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercisegroup>

Some common instructions would go here in the

<introduction>

5.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<p>

<m>f(x)=x^3</m>, <m>\frac{df}{dx}</m>.

This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

</p>

<p>

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group.

For the <c>phrase-global</c> form,

the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the <c>exercises</c> division,

and not the enclosing <c>exercisegroup</c>:

<xref ref="exercises-cosine-derivative" text="phrase-global"/>.

</p>

</exercise>

\(f(x)=x^3\text{,}\) \(\frac{df}{dx}\text{.}\) This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group. For the

phrase-global form, the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the exercises division, and not the enclosing exercisegroup: Exercise 3 of Exercises 11.2.

6.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>y = \cos(x)</m>, <m>y^\prime</m>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

7.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<p>

Compute <m>\int 3x^2\,dx</m>.

</p>

</exercise>

Compute \(\int 3x^2\,dx\text{.}\)

8.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

One of the few things you can place inside of mathematics is a

<q>fill-in</q>

blank.

<idx><h>fill-in blank</h></idx>

We demonstrate a few scenarios here.

See details on syntax in <xref ref="subsection-paragraph-markup" text="type-global"/><ndash/>the use is identical within mathematics.

<ul>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (short, space for <m>x</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin fill="x"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (default, space for <m>XXX</m>):

<m>\sin(<fillin/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside exponents and subscripts

(each is space for the string

<q>12</q>).

In this case,

be sure to wrap your exponents and subscripts in braces,

as would be good <latex/> practice anyway:

<m>x^{5+<fillin fill="12"/>}\,y_{<fillin fill="12"/>}</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside inline math (too long for this line probably, 40 characters long):

<m>\tan(<fillin fill="Mxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx"/>)</m>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

So use inside a displayed equation

<md>

16\log\space<fillin fill="1-x^2"/>

</md>

like this one.

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

Inside the second line of a multi-line display:

<md>

<mrow>y &= x^7\,x^8</mrow>

<mrow>&= x^{<fillin fill="15"/>}</mrow>

</md>

</p>

</li>

<li>

<p>

This fillin has the historical <attr>characters</attr> attribute for a fillin inside math:

<m>1+<fillin characters="5"/>+4=10</m>,

which may be more convenient,

but may not side properly in places like subscripts,

superscripts, fractions, limits of integrals, and so on.

</p>

</li>

</ul>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

One of the few things you can place inside of mathematics is a “fill-in” blank. We demonstrate a few scenarios here. See details on syntax in Subsection 4.7–the use is identical within mathematics.

-

Inside exponents and subscripts (each is space for the string “12”). In this case, be sure to wrap your exponents and subscripts in braces, as would be good LaTeX practice anyway: \(x^{5+\fillinmath{12}}\,y_{\fillinmath{12}}\)

-

Inside inline math (too long for this line probably, 40 characters long): \(\tan(\fillinmath{Mxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx})\)

-

So use inside a displayed equation\begin{equation*} 16\log\space\fillinmath{1-x^2} \end{equation*}like this one.

-

Inside the second line of a multi-line display:\begin{align*} y &= x^7\,x^8\\ &= x^{\fillinmath{15}} \end{align*}

-

This fillin has the historical

@charactersattribute for a fillin inside math: \(1+\fillinmath{XXXXX}+4=10\text{,}\) which may be more convenient, but may not side properly in places like subscripts, superscripts, fractions, limits of integrals, and so on.

Exercises 11.3 More Exercises

View Source for exercises

<exercises xml:id="exercises-section-multiple">

<title>More Exercises</title>

<introduction>

<p>

This exercises section should start on a new page in PDF output if the standard publisher file is used.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

This is not a real exercise,

we just want to explain that this is another subsection of exercises,

which has two consecutive exercise groups.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to first exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Only exercise of first group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to first exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to second exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

First exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Second exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to second exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercisegroup cols="4">

<introduction>

<p>

An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> can have a <c>cols</c> attribute taking a value from 2<ndash/>6.

Exercises will progress by row, in so many columns.

On a small screen,

the HTML exercises may reorganize into fewer columns.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

<p>

And a bit more.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

This feature was designed with short

<q>drill</q>

exercises in mind.

With long exercises,

or exercises with long hints, answers, or solutions,

there is a risk that the <latex/> output will have bad page breaks in the vicinity

(just before)

such an exercise that occupies too much vertical space.

Edit, rearrange,

or use fewer columns to see if the situation improves.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Make a table and a graph for the function <m>f(x)=x^2</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<sidebyside>

<tabular halign="center">

<row header="yes" bottom="medium">

<cell><m>x</m></cell>

<cell><m>f(x)</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>2</m></cell>

<cell><m>4</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>3</m></cell>

<cell><m>9</m></cell>

</row>

</tabular>

<image xml:id="x-squared">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}

\begin{axis}

\addplot[domain=-1.5:4, blue, thick, {stealth}-{stealth}] {x^2};

\end{axis}

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</sidebyside>

</answer>

</exercise>

</exercises>

This exercises section should start on a new page in PDF output if the standard publisher file is used.

1.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

This is not a real exercise,

we just want to explain that this is another subsection of exercises,

which has two consecutive exercise groups.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

This is not a real exercise, we just want to explain that this is another subsection of exercises, which has two consecutive exercise groups.

Exercise Group.

View Source for exercisegroup

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to first exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Only exercise of first group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to first exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

Introduction to first exercise group.

2.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Only exercise of first group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

Only exercise of first group.

Conclusion to first exercise group.

Exercise Group.

View Source for exercisegroup

<exercisegroup>

<introduction>

<p>

Introduction to second exercise group.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

First exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Second exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion to second exercise group.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

Introduction to second exercise group.

3.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

First exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

First exercise of second group.

4.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Second exercise of second group.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

Second exercise of second group.

Conclusion to second exercise group.

Exercise Group.

View Source for exercisegroup

<exercisegroup cols="4">

<introduction>

<p>

An <tag>exercisegroup</tag> can have a <c>cols</c> attribute taking a value from 2<ndash/>6.

Exercises will progress by row, in so many columns.

On a small screen,

the HTML exercises may reorganize into fewer columns.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

<p>

And a bit more.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<p>

This feature was designed with short

<q>drill</q>

exercises in mind.

With long exercises,

or exercises with long hints, answers, or solutions,

there is a risk that the <latex/> output will have bad page breaks in the vicinity

(just before)

such an exercise that occupies too much vertical space.

Edit, rearrange,

or use fewer columns to see if the situation improves.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercisegroup>

An

<exercisegroup> can have a cols attribute taking a value from 2–6. Exercises will progress by row, in so many columns. On a small screen, the HTML exercises may reorganize into fewer columns.

5.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(1+2\)

6.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

\(3+4+5\)

Hint.

7.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(5+6\)

8.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

Add seven to eight.

9.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(9+10\)

10.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(1+2\)

11.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

<p>

And a bit more.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

\(3+4+5\)

Hint.

Solution.

View Source for solution

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

<p>

And a bit more.

</p>

</solution>

Proof.

View Source for proof

<proof>

<p>

A simple argument.

</p>

</proof>

A simple argument.

And a bit more.

12.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(5+6\)

13.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

Add seven to eight.

14.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(9+10\)

15.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(1+2\)

16.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

\(3+4+5\)

Hint.

17.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(5+6\)

18.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

Add seven to eight.

19.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(9+10\)

20.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>1+2</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(1+2\)

21.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>3+4+5</m>

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Addition is associative.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

<m>12</m>

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

First, add <m>3</m> and <m>4</m> to get <m>7</m>,

then add <m>5</m> to arrive at <m>12</m>.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

\(3+4+5\)

Hint.

22.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>5+6</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(5+6\)

23.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Add seven to eight.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<p>

<m>15</m>

</p>

</answer>

</exercise>

Add seven to eight.

24.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

<m>9+10</m>

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

\(9+10\)

This feature was designed with short “drill” exercises in mind. With long exercises, or exercises with long hints, answers, or solutions, there is a risk that the LaTeX output will have bad page breaks in the vicinity (just before) such an exercise that occupies too much vertical space. Edit, rearrange, or use fewer columns to see if the situation improves.

25.

View Source for exercise

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Make a table and a graph for the function <m>f(x)=x^2</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<answer>

<sidebyside>

<tabular halign="center">

<row header="yes" bottom="medium">

<cell><m>x</m></cell>

<cell><m>f(x)</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>2</m></cell>

<cell><m>4</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>3</m></cell>

<cell><m>9</m></cell>

</row>

</tabular>

<image xml:id="x-squared">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}

\begin{axis}

\addplot[domain=-1.5:4, blue, thick, {stealth}-{stealth}] {x^2};

\end{axis}

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</sidebyside>

</answer>

</exercise>

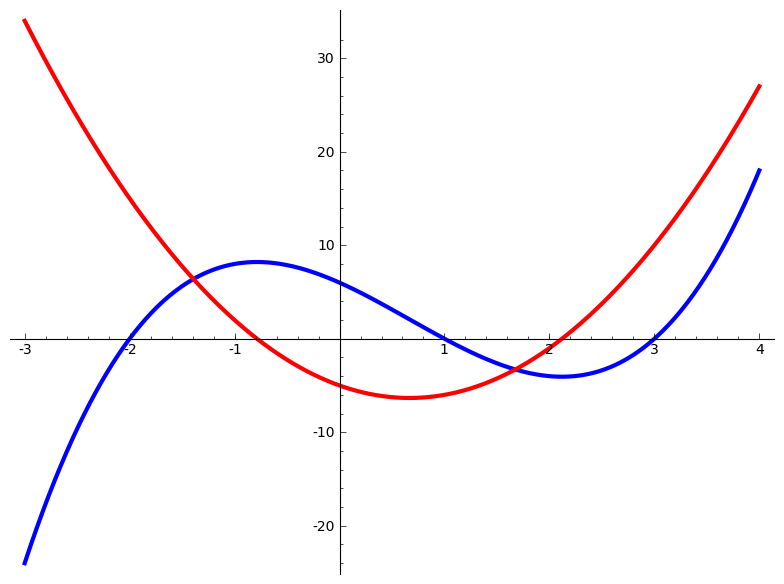

Make a table and a graph for the function \(f(x)=x^2\text{.}\)

Answer.

View Source for answer

<answer>

<sidebyside>

<tabular halign="center">

<row header="yes" bottom="medium">

<cell><m>x</m></cell>

<cell><m>f(x)</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

<cell><m>0</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

<cell><m>1</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>2</m></cell>

<cell><m>4</m></cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell><m>3</m></cell>

<cell><m>9</m></cell>

</row>

</tabular>

<image xml:id="x-squared">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}

\begin{axis}

\addplot[domain=-1.5:4, blue, thick, {stealth}-{stealth}] {x^2};

\end{axis}

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</sidebyside>

</answer>

| \(x\) | \(f(x)\) |

|---|---|

| \(0\) | \(0\) |

| \(1\) | \(1\) |

| \(2\) | \(4\) |

| \(3\) | \(9\) |

References 11.4 References

View Source for references

<references xml:id="references-section">

<title>References</title>

<idx><h>references</h><h>within a section</h></idx>

<introduction>

<p>

These items are here to test basic formatting of references.

</p>

</introduction>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-strang-article">

Gilbert Strang,

<title>The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra</title>,

<journal>The American Mathematical Monthly</journal>

November 1993,

<volume>100</volume>

<number>9</number>,

848<ndash/>855.

</biblio>

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="CF">

<author>

J. B. Conrey and D. W. Farmer

</author>

<title>Mean values of <m>L</m>-functions and symmetry</title>

<journal>Internat. Math. Res. Notices</journal>

<number>17</number>

<year>2000</year>

<pages start="883" end="908"/>

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-beezer-fcla">

Robert A. Beezer,

<title>A First Course in Linear Algebra</title>,

3rd Edition, Congruent Press, 2012.

<note>

<p>

An online, open-source<fn>

A gratuitous footnote to test prior bug confusing this with a REMARK-LIKE <tag>note</tag>.

</fn> offering.

</p>

</note>

</biblio>

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="Dav">

<author>

H. Davenport

</author>

<title>Multiplicative Number Theory</title>

<series>GTM</series>

<volume>74</volume>

<publisher>Springer-Verlag New York, NY</publisher>

<year>2000</year>

<pages>xiv+177</pages>

<pubnote>A note may accompany a bibliographic item, such as saying the manuscript is under review. But it cannot contain any formatting.</pubnote>

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional">

Alexander Rosswell,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2020</year>,

<volume>2</volume>

<number>6</number>,

884<ndash/>888.

</biblio>

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional-two">

<ibid/>,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles, Part 2</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2021</year>,

<volume>3</volume>

<number>4</number>,

102<ndash/>103.

</biblio>

<conclusion>

<p>

This is a conclusion, which has not been used very much in this sample.

Did you see that the entry for <xref ref="biblio-beezer-fcla"/> has a short annotation?

So you can make annotated bibliographies easily.

</p>

</conclusion>

</references>

These items are here to test basic formatting of references.

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-strang-article">

Gilbert Strang,

<title>The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra</title>,

<journal>The American Mathematical Monthly</journal>

November 1993,

<volume>100</volume>

<number>9</number>,

848<ndash/>855.

</biblio>

[1]

Gilbert Strang, The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra, The American Mathematical Monthly November 1993, 100 no. 9, 848–855.

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="CF">

<author>

J. B. Conrey and D. W. Farmer

</author>

<title>Mean values of <m>L</m>-functions and symmetry</title>

<journal>Internat. Math. Res. Notices</journal>

<number>17</number>

<year>2000</year>

<pages start="883" end="908"/>

</biblio>

[2]

J. B. Conrey and D. W. Farmer, Mean values of \(L\)-functions and symmetry, Internat. Math. Res. Notices no. 17, (2000) pp. 883-908.

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-beezer-fcla">

Robert A. Beezer,

<title>A First Course in Linear Algebra</title>,

3rd Edition, Congruent Press, 2012.

<note>

<p>

An online, open-source<fn>

A gratuitous footnote to test prior bug confusing this with a REMARK-LIKE <tag>note</tag>.

</fn> offering.

</p>

</note>

</biblio>

[3]

Robert A. Beezer, A First Course in Linear Algebra, 3rd Edition, Congruent Press, 2012.

Note.

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="bibtex" xml:id="Dav">

<author>

H. Davenport

</author>

<title>Multiplicative Number Theory</title>

<series>GTM</series>

<volume>74</volume>

<publisher>Springer-Verlag New York, NY</publisher>

<year>2000</year>

<pages>xiv+177</pages>

<pubnote>A note may accompany a bibliographic item, such as saying the manuscript is under review. But it cannot contain any formatting.</pubnote>

</biblio>

[4]

H. Davenport, Multiplicative Number Theory, GTM 74 Springer-Verlag New York, NY; (2000) xiv+177. [A note may accompany a bibliographic item, such as saying the manuscript is under review. But it cannot contain any formatting.]

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional">

Alexander Rosswell,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2020</year>,

<volume>2</volume>

<number>6</number>,

884<ndash/>888.

</biblio>

[5]

Alexander Rosswell, Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles, Mathematicians of America (2020), 2 no. 6, 884–888.

View Source for biblio

<biblio type="raw" xml:id="biblio-rosswell-fictional-two">

<ibid/>,

<title>Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles, Part 2</title>,

<journal>Mathematicians of America</journal>

<year>2021</year>,

<volume>3</volume>

<number>4</number>,

102<ndash/>103.

</biblio>

[6]

Ibid., Diffeomorphisms of Penciled Fiber Bundles, Part 2, Mathematicians of America (2021), 3 no. 4, 102–103.