<section xml:id="worksheets" label="section-worksheets">

<title>Worksheets</title>

<introduction>

<title>About Worksheets</title>

<p>

This is a section full of worksheets.

Each is a division of its own,

via the <tag>worksheet</tag> element.

This is an optional <tag>introduction</tag> to the current <tag>section</tag>.

In practice you might want to rip out all the worksheets of an entire book and bundle them up as an

<q>activity book.</q>

</p>

<p>

If you make PDF output you will notice an increased amount of control over layout.

Also, if the publication file elects <latex/> draft mode,

then there will be visual indicators of prescribed whitespace.

</p>

</introduction>

<worksheet label="worksheet-geometric-prelude">

<title>A Geometric Prelude (without authored pages)</title>

<!-- <author>Dave Rosoff</author> -->

<objectives xml:id="objectives">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

<introduction>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has the default (skinny) margins.

</p>

<p>

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier,

that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane

(even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not).

In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram,

as pictured in <xref ref="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

<sidebyside width="30%">

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

</sidebyside>

<p>

In this exercise,

we'll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle

(<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors" text="type-global"/>)

intersect at a point.

Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges,

as in the figure.

We'll do this in a few steps.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<p>

<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians" text="type-global"/> from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

</p>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy" width="50%">

<description><p>

The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>,

<m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.

This image description should show up in the regular view,

but disappear when printing.

</p></description>

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<sidebyside margins="0%" widths="30% 60%" valign="top">

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<title>Wrap-up</title>

<p>

It's possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way:

we didn't specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

</p>

</conclusion>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-geometric-prelude-pages">

<title>A Geometric Prelude (with authored pages)</title>

<!-- <author>Dave Rosoff</author> -->

<objectives xml:id="objectives-pages">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

<introduction>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has the default (skinny) margins.

</p>

<p>

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier,

that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane

(even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not).

In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram,

as pictured in <xref ref="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

<sidebyside width="30%">

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

</sidebyside>

<p>

In this exercise,

we'll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle

(<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors" text="type-global"/>)

intersect at a point.

Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges,

as in the figure.

We'll do this in a few steps.

</p>

</introduction>

<page>

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic-pages" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</page>

<page>

<p>

<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians" text="type-global"/> from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

</p>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<sidebyside margins="0%" widths="30% 60%" valign="top">

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition-pages" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

</page>

<conclusion>

<title>Wrap-up</title>

<p>

It's possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way:

we didn't specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

</p>

</conclusion>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-networks" top="3cm" bottom="1.2in">

<title>Networks Worksheet (no authored pages)</title>

<!-- <subtitle>An Activity Using Linear Algebra to Solve Network Applications</subtitle> -->

<introduction>

<title>Basic laws for electrical circuits</title>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Virgil Pierce at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has default (skinny) left and right margins,

but we have specified longer top and bottom margins,

with the top being the larger of the two.

</p>

<theorem>

<title>Ohms Law</title>

<p>

The current through a resistor is proportional to the ratio of the <em> Voltage </em>

to the <em> Resistance </em>

<md>

I = \frac{V}{R}

</md>

Or for our purposes

<md>

I R = V

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<theorem>

<title>Kirchoffs Current Law</title>

<p>

The sum of the currents in a network meeting at a point is zero.

<md>

\sum_{k=1}^n I_k = 0

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<example>

<title>Kirchoff's Current Law</title>

<p>

For the circuit below <m> I_1 + I_2 = I_3 </m>.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-kirchoff-law" width="40%">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_1$, *-o](2,2);

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_2$, *-o](2,-2);

\draw (-3, 0)

to[R, i=$I_3$, o-*](0,0);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</example>

<theorem>

<title>Kirchoffs Voltage Law</title>

<p>

The sum of the voltages around any closed circuit

(or subcircuit)

is zero.

<md>

\sum_{k=1}^n V_k = 0

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<p>

Kirchoffs Current Law and Kirkoffs Voltage Law combined with Ohms Law gives for any circuit of resistors and sources a linear system that may

(or may not)

determine the currents.

</p>

</introduction>

<sidebyside width="45%" margins="0%">

<exercise workspace="1.5in">

<statement>

<p>

For the simple network pictured,

calculuate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-simple-network">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw (0,0)

to[V, v=$11\quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](2,3)

to[R, R=$4\quad \mbox{ohm}$] (3, 3)

to[short](4,3)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,0)

to[short](3,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](2,0)

to[short](0,0);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

Compare it with a parallel circuit network.

Calculate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-parallel-circuit">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw(0,0)

to[V, v=$11\quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](5,3)

to[R, R=$4\quad \mbox{ohm}$](6,3)

to[short](7,3)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](7,0)

to[short](6,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](5,0)

to[short](0,0);

\draw(4,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,3);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Now for a more complicated network.

Calculate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-complicated-network">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw(0,0)

to[V, v=$11 \quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](5,3)

to[R, R=$4 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](6,3)

to[short](9,3)

to[R, R=$4 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](10,3)

to[short](11,3)

to[R, R=$3 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](11, 0)

to[short](10,0)

to[R, R=$2\quad \mbox{ohm}$](9,0)

to[short](6,0)

to[R, R=$2\quad \mbox{ohm}$](5,0)

to[short](0,0);

\draw(4,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,3);

\draw(8,0)

to[R, R=$1\quad \mbox{ohm}$](8,3);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="3in">

<statement>

<p>

Now generalize these ideas to a context outside of electrical circuits.

Consider the network of streets given in the diagram

(with one-way directions as indicated).

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-street-network" width="65%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[>=stealth]

\draw[->, very thick] (0,0) -- (10, 0) node[midway, below]{East Bound Winooski Ave};

\draw[<-, very thick] (0, 1) -- (10, 1) node[midway, above]{West Bound Winooski Ave};

\draw[<-, very thick] (0, 4) -- (10, 4) node[midway, above]{Shelburne St};

\draw[<-, very thick] (1, -1) -- (1, 5) node[midway, above, sloped]{Willow};

\draw[->, very thick] (9, -1) -- (9, 5) node[midway, above, sloped]{Jay};

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

<p>

A traffic engineer counts the hourly flow of cars into and out of this network at the entrances.

They get (EB = East Bound; WB = West Bound):

</p>

<table>

<title>Estimated hourly traffic flow for the road network</title>

<tabular row-headers="yes" halign="center">

<row header="yes">

<cell/>

<cell>EB Winooski</cell>

<cell>WB Winooski</cell>

<cell>Shelburne St</cell>

<cell>Willow</cell>

<cell>Jay</cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell halign="left">into</cell>

<cell>50</cell>

<cell>400</cell>

<cell>0</cell>

<cell>10</cell>

<cell>50</cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell halign="left">out of</cell>

<cell>55</cell>

<cell>390</cell>

<cell>20</cell>

<cell>15</cell>

<cell>30</cell>

</row>

</tabular>

</table>

<p>

Use a variable for each segment inside of the network and set up a system of linear equations restricting the flow.

Solve the system.

Note that you should not get a unique solution as traffic should be able to flow through the network in various ways.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-networks-pages" top="3cm" bottom="1.2in">

<title>Networks Worksheet (with authored pages)</title>

<!-- <subtitle>An Activity Using Linear Algebra to Solve Network Applications</subtitle> -->

<introduction>

<title>Basic laws for electrical circuits</title>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Virgil Pierce at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has default (skinny) left and right margins,

but we have specified longer top and bottom margins,

with the top being the larger of the two.

</p>

<theorem>

<title>Ohms Law</title>

<p>

The current through a resistor is proportional to the ratio of the <em> Voltage </em>

to the <em> Resistance </em>

<md>

I = \frac{V}{R}

</md>

Or for our purposes

<md>

I R = V

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<theorem>

<title>Kirchoffs Current Law</title>

<p>

The sum of the currents in a network meeting at a point is zero.

<md>

\sum_{k=1}^n I_k = 0

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<example>

<title>Kirchoff's Current Law</title>

<p>

For the circuit below <m> I_1 + I_2 = I_3 </m>.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-kirchoff-law-pages" width="40%">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_1$, *-o](2,2);

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_2$, *-o](2,-2);

\draw (-3, 0)

to[R, i=$I_3$, o-*](0,0);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</example>

<theorem>

<title>Kirchoffs Voltage Law</title>

<p>

The sum of the voltages around any closed circuit

(or subcircuit)

is zero.

<md>

\sum_{k=1}^n V_k = 0

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<p>

Kirchoffs Current Law and Kirkoffs Voltage Law combined with Ohms Law gives for any circuit of resistors and sources a linear system that may

(or may not)

determine the currents.

</p>

</introduction>

<page>

</page>

<page>

<sidebyside width="45%" margins="0%">

<exercise workspace="1.5in">

<statement>

<p>

For the simple network pictured,

calculuate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-simple-network-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw (0,0)

to[V, v=$11\quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](2,3)

to[R, R=$4\quad \mbox{ohm}$] (3, 3)

to[short](4,3)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,0)

to[short](3,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](2,0)

to[short](0,0);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

Compare it with a parallel circuit network.

Calculate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-parallel-circuit-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw(0,0)

to[V, v=$11\quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](5,3)

to[R, R=$4\quad \mbox{ohm}$](6,3)

to[short](7,3)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](7,0)

to[short](6,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](5,0)

to[short](0,0);

\draw(4,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,3);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Now for a more complicated network.

Calculate the amperage in each part of the network by setting up a system of linear equations for the amperages.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-complicated-network-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw(0,0)

to[V, v=$11 \quad \mbox{volt}$](0, 3)

to[short](5,3)

to[R, R=$4 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](6,3)

to[short](9,3)

to[R, R=$4 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](10,3)

to[short](11,3)

to[R, R=$3 \quad \mbox{ohm}$](11, 0)

to[short](10,0)

to[R, R=$2\quad \mbox{ohm}$](9,0)

to[short](6,0)

to[R, R=$2\quad \mbox{ohm}$](5,0)

to[short](0,0);

\draw(4,0)

to[R, R=$3\quad \mbox{ohm}$](4,3);

\draw(8,0)

to[R, R=$1\quad \mbox{ohm}$](8,3);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

</page>

<page>

<exercise workspace="3in">

<statement>

<p>

Now generalize these ideas to a context outside of electrical circuits.

Consider the network of streets given in the diagram

(with one-way directions as indicated).

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-street-network-pages" width="65%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[>=stealth]

\draw[->, very thick] (0,0) -- (10, 0) node[midway, below]{East Bound Winooski Ave};

\draw[<-, very thick] (0, 1) -- (10, 1) node[midway, above]{West Bound Winooski Ave};

\draw[<-, very thick] (0, 4) -- (10, 4) node[midway, above]{Shelburne St};

\draw[<-, very thick] (1, -1) -- (1, 5) node[midway, above, sloped]{Willow};

\draw[->, very thick] (9, -1) -- (9, 5) node[midway, above, sloped]{Jay};

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

<p>

A traffic engineer counts the hourly flow of cars into and out of this network at the entrances.

They get (EB = East Bound; WB = West Bound):

</p>

<table>

<title>Estimated hourly traffic flow for the road network</title>

<tabular row-headers="yes" halign="center">

<row header="yes">

<cell/>

<cell>EB Winooski</cell>

<cell>WB Winooski</cell>

<cell>Shelburne St</cell>

<cell>Willow</cell>

<cell>Jay</cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell halign="left">into</cell>

<cell>50</cell>

<cell>400</cell>

<cell>0</cell>

<cell>10</cell>

<cell>50</cell>

</row>

<row>

<cell halign="left">out of</cell>

<cell>55</cell>

<cell>390</cell>

<cell>20</cell>

<cell>15</cell>

<cell>30</cell>

</row>

</tabular>

</table>

<p>

Use a variable for each segment inside of the network and set up a system of linear equations restricting the flow.

Solve the system.

Note that you should not get a unique solution as traffic should be able to flow through the network in various ways.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</page>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-testing" margin="1cm">

<introduction>

<p>

This is a mock one-page worksheet for testing purposes.

We have specified an overall margin just slightly less than the default.

</p>

</introduction>

<sidebyside width="45%" margins="0%">

<exercise workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Integer sagittis dictum turpis vel aliquet.

Fusce ut suscipit dolor, nec tristique nisl.

Aenean luctus, leo et ornare fermentum,

nibh dui vulputate leo, nec tincidunt augue ipsum sed odio.

Nunc non erat sollicitudin, iaculis eros consequat, dapibus eros.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

This is a hint.

You can hide it in the print preview before printing.

</p>

</hint>

<answer>

<p>

Here is an answer.

Also hidable.

</p>

</answer>

<solution>

<p>

This is a rather long solution.

When you hide or show it in the print preview,

the workspace should be adjusted

(the page will reload).

</p>

<p>

Integer sagittis dictum turpis vel aliquet.

Fusce ut suscipit dolor, nec tristique nisl.

Aenean luctus, leo et ornare fermentum,

nibh dui vulputate leo, nec tincidunt augue ipsum sed odio.

Nunc non erat sollicitudin, iaculis eros consequat, dapibus eros.

</p>

</solution>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<p>

A two-line paragraph interspersed to check on spacing,

breaks and all that.

</p>

<exercise workspace="1.5in">

<title>A full-width exercise</title>

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

<p>

Integer sagittis dictum turpis vel aliquet.

Fusce ut suscipit dolor, nec tristique nisl.

Aenean luctus, leo et ornare fermentum,

nibh dui vulputate leo, nec tincidunt augue ipsum sed odio.

Nunc non erat sollicitudin, iaculis eros consequat, dapibus eros.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<p>

Another two-line paragraph interspersed to check on spacing,

breaks and all that.

</p>

<sidebyside width="30%" margins="0%">

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="0.5in">

<!-- <title>The Tallest</title> -->

<statement>

<p>

Integer sagittis dictum turpis vel aliquet.

Fusce ut suscipit dolor, nec tristique nisl.

Aenean luctus, leo et ornare fermentum,

nibh dui vulputate leo, nec tincidunt augue ipsum sed odio.

Nunc non erat sollicitudin, iaculis eros consequat, dapibus eros.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<activity>

<title>A Mock Activity</title>

<statement>

<p>

The problem, as we see it.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

A worksheet could have hints, no?

But no spacing.

Note row below has widths set to balance the heights.

</p>

</hint>

</activity>

<sidebyside widths="25% 40% 25%" margins="0%">

<exercise workspace="0.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="0.5in">

<!-- <title>Balanced Heights</title> -->

<statement>

<p>

Integer sagittis dictum turpis vel aliquet.

Fusce ut suscipit dolor, nec tristique nisl.

Aenean luctus, leo et ornare fermentum,

nibh dui vulputate leo, nec tincidunt augue ipsum sed odio.

Nunc non erat sollicitudin, iaculis eros consequat, dapibus eros.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="0.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Praesent rutrum scelerisque felis sit amet adipiscing.

Phasellus in mollis velit.

Nunc malesuada felis sit amet massa cursus,

eget elementum neque viverra.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-dot-products" courseid="MAT-150" series="Activity" seriescode="13">

<title>Dot products and projection</title>

<sidebyside width="45%" margins="0%">

<exercise>

<introduction>

<p>

Let <m>{\vec v}_1 = (-4,1)</m>,

<m>{\vec v}_2 = (2,2)</m>,

<m>{\vec v}_3 = (1,2,3)</m>, <m>{\vec v}_4 = (-2,1,0)</m>.

Find the values of the following expressions:

</p>

</introduction>

<task workspace="1in">

<p>

<m>{\vec v}_1 \cdot {\vec v}_2 = <fillin/></m>

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="1.0in">

<p>

<m>{\vec v}_3 \cdot {\vec v}_4 = <fillin/></m>

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="1in">

<p>

<m>\lVert{\vec v}_1\rVert = <fillin/></m>

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="1in">

<p>

<m>\lVert{\vec v}_4\rVert = <fillin/></m>

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="1in">

<p>

Are any of these vectors perpendicular to each other?

<fillin/>

</p>

</task>

</exercise>

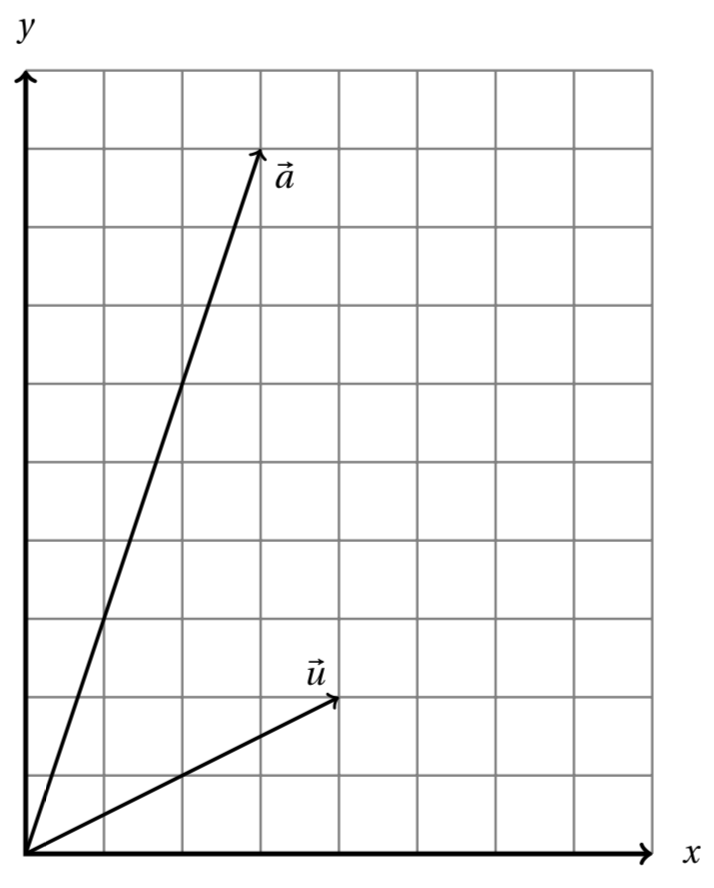

<exercise workspace="3in">

<statement>

<p>

The vectors <m>\vec a = (3,9)</m> and <m>\vec u = (4,2)</m> are pictured below.

Derive the formula for projection on a line and use it to find the projection of <m>\vec a</m> on the line spanned by <m>\vec u</m>.

Also compute the length of the residual vector.

</p>

<image width="100%" source="images/projection1.png">

<shortdescription>two vectors in a Cartesian plane</shortdescription>

</image>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<sidebyside width="48%" margins="0%">

<exercise workspace="1.25in">

<introduction>

<p>

Consider the vector equation

<md>

m \begin{bmatrix}2 \\ 5\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}3 \\ 7\end{bmatrix}

</md>.

</p>

</introduction>

<task>

<p>

Check that there is no solution <m>m</m> that makes the equation true.

</p>

</task>

<task>

<p>

Use projection to find the best approximation <m>\hat m</m>.

</p>

</task>

<task>

<p>

Compute <m>\hat m \begin{bmatrix}2 \\ 5\end{bmatrix} </m>.

</p>

</task>

<task>

<p>

Compute the residual vector.

</p>

</task>

<task>

<p>

Compute the length of the residual vector and explain what it means.

</p>

</task>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<introduction>

<p>

Consider the system of equations

<md>

<mrow>3t \amp =5</mrow>

<mrow>2t \amp = 9</mrow>

</md>.

</p>

</introduction>

<task workspace="2in">

<p>

Write the system in vector form.

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="3.9in">

<p>

Find the best estimate, <m>\hat t</m>,

of <m>t</m> using projection.

</p>

</task>

<task workspace="2in">

<p>

Compute the length of the residual vector.

</p>

</task>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-activity-no-task">

<activity workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Just a simple activity here.

</p>

</statement>

</activity>

<activity workspace="1in">

<statement>

<p>

Here is a second activity.

</p>

</statement>

</activity>

</worksheet>

<worksheet label="worksheet-activity-with-task">

<activity>

<introduction>

<p>

This is going to be an activity with tasks.

</p>

</introduction>

<task workspace="0.75in">

<statement>

<p>

Here is the first task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<task workspace="0.25in">

<statement>

<p>

Here is the second task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<task workspace="1.75in">

<statement>

<p>

Here is the third task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<conclusion>

<p>

This is a conclusion that comes after the last task.

</p>

</conclusion>

</activity>

</worksheet>

<!-- NB: this is duplicated in the sample article -->

<worksheet label="worksheet-exercisegroup" margin="1cm">

<introduction>

<p>

This is a mock worksheet for testing the use of <attr>workspace</attr> for <tag>exercise</tag> within an <tag>exercisegroup</tag>.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercisegroup cols="2" workspace="1in">

<introduction>

<p>

Do things to the following.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Apple

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Banana

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Cherry

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Durian

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

Elderberry (with workspace override)

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Fig

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Guava

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Habanero

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

I can't think of an

<q>I</q>

fruit.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Jackfruit

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercisegroup>

<exercisegroup workspace="0.25in">

<introduction>

<p>

Now with one column, do things to the following.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Apple

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Banana

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Cherry

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Durian

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

Elderberry (with workspace override)

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Fig

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Guava

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Habanero

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

I can't think of an

<q>I</q>

fruit.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<exercise>

<statement>

<p>

Jackfruit

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</exercisegroup>

</worksheet>

<worksheet>

<title>Worksheet with an exercise with tasks and subtasks</title>

<introduction>

<p>

Page breaking between tasks in a single exercise can be tricky.

This is a test for that.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise>

<introduction>

<p>

Here are multiple tasks with just enough workspace to cause a page break after the third one.

</p>

</introduction>

<task>

<introduction>

<p>

This task has two short subtasks that should be indented under it.

</p>

</introduction>

<task workspace=".5in">

<statement>

<p>

The first subtask.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<task workspace=".5in">

<statement>

<p>

The second subtask.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion for the first task.

</p>

</conclusion>

</task>

<task workspace="1.5in">

<statement>

<p>

The second task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<task workspace="1.5in">

<statement>

<p>

The third task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<task workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

The fourth task.

</p>

</statement>

</task>

<conclusion>

<p>

Conclusion for the entire exercise.

</p>

</conclusion>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="3in">

<statement>

<p>

An exercise without any tasks but some workspace.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</worksheet>

</section>

Print preview

Section 36 Worksheets

View Source for section

About Worksheets.

This is a section full of worksheets. Each is a division of its own, via the

<worksheet> element. This is an optional <introduction> to the current <section>. In practice you might want to rip out all the worksheets of an entire book and bundle them up as an “activity book.”

If you make PDF output you will notice an increased amount of control over layout. Also, if the publication file elects LaTeX draft mode, then there will be visual indicators of prescribed whitespace.

Worksheet 36.1 A Geometric Prelude (without authored pages)

View Source for worksheet

<worksheet label="worksheet-geometric-prelude">

<title>A Geometric Prelude (without authored pages)</title>

<!-- <author>Dave Rosoff</author> -->

<objectives xml:id="objectives">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

<introduction>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has the default (skinny) margins.

</p>

<p>

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier,

that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane

(even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not).

In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram,

as pictured in <xref ref="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

<sidebyside width="30%">

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

</sidebyside>

<p>

In this exercise,

we'll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle

(<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors" text="type-global"/>)

intersect at a point.

Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges,

as in the figure.

We'll do this in a few steps.

</p>

</introduction>

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

<p>

<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians" text="type-global"/> from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

</p>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy" width="50%">

<description><p>

The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>,

<m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.

This image description should show up in the regular view,

but disappear when printing.

</p></description>

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<sidebyside margins="0%" widths="30% 60%" valign="top">

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

<conclusion>

<title>Wrap-up</title>

<p>

It's possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way:

we didn't specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

</p>

</conclusion>

</worksheet>

Objectives

View Source for objectives

<objectives xml:id="objectives">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

-

Practice visualizing vector addition

-

Use vectors without explicit coordinates

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August 2018. It has the default (skinny) margins.

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier, that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane (even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not). In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram, as pictured in Figure 36.1.

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

In this exercise, we’ll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle (Figure 36.2) intersect at a point. Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges, as in the figure. We’ll do this in a few steps.

1.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

What is the value of \(\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}\text{?}\)

Figure 36.3 from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy" width="50%">

<description><p>

The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>,

<m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.

This image description should show up in the regular view,

but disappear when printing.

</p></description>

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

The medians of the triangle are \(\vec{M}_1\text{,}\) \(\vec{M}_2\text{,}\) and \(\vec{M}_3\text{.}\) This image description should show up in the regular view, but disappear when printing.

2.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

Show that \(\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0\text{.}\)

Hint.

View Source for hint

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

3.

View Source for exercise

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

To show that the point \(P\) exists (as the common intersection of the \(\vec{M}_{i}\)), show that

\begin{equation*}

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = \fillinmath{\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}}\text{.}

\end{equation*}

4.

View Source for exercise

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

If you have time, try to devise a vector proof of Euclid’s result presented at the beginning of the workshop. Recall that a parallelogram is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

Wrap-up.

It’s possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way: we didn’t specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

Worksheet 36.2 A Geometric Prelude (with authored pages)

View Source for worksheet

<worksheet label="worksheet-geometric-prelude-pages">

<title>A Geometric Prelude (with authored pages)</title>

<!-- <author>Dave Rosoff</author> -->

<objectives xml:id="objectives-pages">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

<introduction>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has the default (skinny) margins.

</p>

<p>

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier,

that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane

(even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not).

In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram,

as pictured in <xref ref="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

<sidebyside width="30%">

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

</sidebyside>

<p>

In this exercise,

we'll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle

(<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors" text="type-global"/>)

intersect at a point.

Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges,

as in the figure.

We'll do this in a few steps.

</p>

</introduction>

<page>

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic-pages" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</page>

<page>

<p>

<xref ref="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians" text="type-global"/> from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

</p>

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

<sidebyside margins="0%" widths="30% 60%" valign="top">

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition-pages" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

</sidebyside>

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

</page>

<conclusion>

<title>Wrap-up</title>

<p>

It's possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way:

we didn't specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

</p>

</conclusion>

</worksheet>

Objectives

View Source for objectives

<objectives xml:id="objectives-pages">

<ul>

<li>Practice visualizing vector addition</li>

<li>Use vectors without explicit coordinates</li>

</ul>

</objectives>

-

Practice visualizing vector addition

-

Use vectors without explicit coordinates

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Dave Rosoff at a CuratedCourses workshop in August 2018. It has the default (skinny) margins.

It was known to Euclid, and probably earlier, that the midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral all lie in the same plane (even if the vertices of the quadrilateral do not). In fact, these midpoints are the vertices of a parallelogram, as pictured in Figure 36.1.

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<caption>The midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-midpoints-of-quadrilateral-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=0.8, yscale=0.8]

\draw[style={black, ultra thick}] (0,0) -- (5,0) -- (4,4) -- (2,5) -- (0,0);

\draw[style={black, dashed, very thick}] (2.5, 0) -- (4.5, 2) -- (3, 4.5) -- (1, 2.5) -- (2.5, 0);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<caption>The sides of a triangle presented as vectors.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-vectors-pages">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

% \draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

% {} -- (1.5,0) node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

% {} -- (2,1) node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

%\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

% {} -- (0.5,1) node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

%\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

%\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

In this exercise, we’ll use vectors to show that the medians of any triangle (Figure 36.2) intersect at a point. Recall that medians are the lines connecting the vertices of the triangle to the midpoints of their opposite edges, as in the figure. We’ll do this in a few steps.

1.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="ex-cyclic-pages" workspace="4in">

<statement>

<p>

What is the value of <m>\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}</m>?

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

What is the value of \(\vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}\text{?}\)

Figure 36.3 from the previous page is reproduced for your convenience.

View Source for figure

<figure xml:id="figure-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages">

<caption>The medians of the triangle are <m>\vec{M}_1</m>, <m>\vec{M}_2</m>, and <m>\vec{M}_3</m>.</caption>

<image xml:id="worksheet-triangle-cyclic-medians-copy-pages" width="50%">

<latex-image>

\begin{tikzpicture}[xscale=1.5, yscale=1.5]

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (0,0) -- (2.30 , 0) node [below] {$\vec{A}$} -- (3,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (3,0) -- (1.47, 1.53) node [above right =1mm] {$\vec{B}$} -- (1,2);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black, thick}] (1,2) -- (0.23 , 0.46) node [above left=1mm] {$\vec{C}$} -- (0,0);

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (1,2) -- (7/6, 4/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{1}$} -- (1.5,0);% node[below right=0mm and 3mm] {$\vec{A}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (0,0) -- (2/3, 1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{2}$} -- (2,1);% node[above left=5mm and 1mm] {$\vec{B}$};

\draw[->,>=latex, style={black,semithick,dashed}] (3,0) -- (13/6,1/3) node

{$\vec{M}_{3}$} -- (0.5,1);% node[below left=1mm and 3mm] {$\vec{C}$};

\node[draw,shape=circle,fill=black,name=P,scale=0.5] at (4/3,2/3) {};

\node[above right=1.2mm and -0.5mm of P] at (4/3,2/3) {$P$};

% \node {$P$} (1.3333,0.6667);

\end{tikzpicture}

</latex-image>

</image>

</figure>

2.

View Source for exercise

<exercise xml:id="exercise-vector-addition-pages" workspace="4.5in">

<statement>

<p>

Show that <m>\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0</m>.

</p>

</statement>

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

</exercise>

Show that \(\vec{M}_{1} + \vec{M}_{2} + \vec{M}_{3} = 0\text{.}\)

Hint.

View Source for hint

<hint>

<p>

Use <xref ref="ex-cyclic" text="type-global"/>.

</p>

</hint>

3.

View Source for exercise

<exercise workspace="2in">

<statement>

<p>

To show that the point <m>P</m> exists

(as the common intersection of the <m>\vec{M}_{i}</m>),

show that

<md>

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = <fillin fill="\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}"/>

</md>.

</p>

</statement>

</exercise>

To show that the point \(P\) exists (as the common intersection of the \(\vec{M}_{i}\)), show that

\begin{equation*}

\vec{A} + \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{3} = \frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{2} = \fillinmath{\frac{2}{3} \vec{M}_{1}-\vec{C}}\text{.}

\end{equation*}

4.

View Source for exercise

<exercise workspace="2.54cm">

<p>

If you have time,

try to devise a vector proof of Euclid's result presented at the beginning of the workshop.

Recall that a <term>parallelogram</term>

is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

</p>

</exercise>

If you have time, try to devise a vector proof of Euclid’s result presented at the beginning of the workshop. Recall that a parallelogram is a four-sided polygon whose opposite sides are parallel.

Wrap-up.

It’s possible to do interesting things with vector arithmetic in a coordinate-free way: we didn’t specify an origin, or any entries of any vectors in the examples.

Worksheet 36.3 Networks Worksheet (no authored pages)

View Source for worksheet

<worksheet label="worksheet-networks" top="3cm" bottom="1.2in">

<title>Networks Worksheet (no authored pages)</title>

<!-- <subtitle>An Activity Using Linear Algebra to Solve Network Applications</subtitle> -->

<introduction>

<title>Basic laws for electrical circuits</title>

<p>

This two-page worksheet was generously donated to the sample article by Virgil Pierce at a CuratedCourses workshop in August<nbsp/>2018.

It has default (skinny) left and right margins,

but we have specified longer top and bottom margins,

with the top being the larger of the two.

</p>

<theorem>

<title>Ohms Law</title>

<p>

The current through a resistor is proportional to the ratio of the <em> Voltage </em>

to the <em> Resistance </em>

<md>

I = \frac{V}{R}

</md>

Or for our purposes

<md>

I R = V

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<theorem>

<title>Kirchoffs Current Law</title>

<p>

The sum of the currents in a network meeting at a point is zero.

<md>

\sum_{k=1}^n I_k = 0

</md>

</p>

</theorem>

<example>

<title>Kirchoff's Current Law</title>

<p>

For the circuit below <m> I_1 + I_2 = I_3 </m>.

</p>

<image xml:id="worksheet-kirchoff-law" width="40%">

<latex-image>

\begin{circuitikz}

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_1$, *-o](2,2);

\draw (0,0)

to[R, i=$I_2$, *-o](2,-2);

\draw (-3, 0)

to[R, i=$I_3$, o-*](0,0);

\end{circuitikz}

</latex-image>

</image>